The growing role and value of metadata

Libraries are very used to managing metadata for information resources - for books, images, journal articles and other resources. Metadata practice is rich and varied. We also work with geospatial data, archives, images, and many other specialist resources. Authority work has focused on people, places and things (subjects). Archivists are concerned about evidential integrity, context and provenance. And so on.

In the network environment, general metadata requirements have continued to evolve in various ways:

Information resource diversification. We want to discover, manage or otherwise interact with a progressively broader range of resources, research data, for example, or open educational resources.

Resource type diversification. However, we are also increasingly interested in more resource types than informational alone. The network connects together many entities or types of resource in new ways, and interaction between these entities requires advance knowledge, often provided by metadata, to be efficient. Workflows tie people, applications and devices together to get things done. To be effective, each of these resources needs to be described. Social applications like Strava tie together people, activities, places, and so on. Scholarly engines like Google Scholar, Semantic Scholar, Scopus or Dimensions tie together research outputs, researchers, funders, and institutions. The advance knowledge required for these workflows and environments to work well is provided by metadata and so we are increasingly interested in metadata about a broad range of entities.

Functional diversification. We want to discover, manage, request or buy resources. We also want to provide context about resources, ascertain their validity or integrity over time, determine their provenance. We want to compare resources, collect data about usage, track and measure. We want to make connections between entities, understand relationships, and actually create new knowledge. We do not just want to find individual information resources or people, we want to make sense of networks of people, resources, institutions, and so on and the relations between them.

Source diversification. I have spoken about four sources of metadata in the past. Versions of these are becoming more important, but so is how they are used together to tackle the growing demands on metadata in digital environments.

- Professional. Our primary model of metadata has been a professional one, where librarians, abstract writers, archivists and so on are the primary source. Libraries have streamlined metadata creation and provision for acquired resources. Many libraries, archives and others, devote professional attention and expertise to unique resources - special collections, archives, digitised and born-digital materials, institutional research outputs, faculty profiles, and so on.

- Community. I described the second as crowdsourced, and certainly the collection of contributions in this way has been of importance, in digital projects, community initiatives and in other places. However, one might extend this to a broader community source. The subject of the description or the communities from which the resources originate are an increasingly important source. This is especially the case as we pluralize description as I discuss further below. An interesting example here is Local Contexts which works with collecting institutions and Indigenous communities and "provides a new set of procedural workflows that emphasize vetting content, collaborative curation, ethical management and sustained outreach practices within institutions."

- Programmatically promoted. The programmatic promotion of metadata is becoming increasingly important. We will see more algorithmically generated metadata, as natural language processing, entity recognition, machine learning, image recognition, and other approaches become more common. This is especially the case as we move towards more entity-based approaches where the algorithmic identification of entities and relationships across various resources becomes important. At the same time, we are more aware of the need for responsible operations, where dominant perspectives also influence construction of algorithms and learning sets.

- Intentional. A fourth source is intentional data, or usage data, data about how resources are downloaded, cited, linked and so on. This may be used to rate and rank, or to refine other descriptions. Again, appropriate use of this data needs to be responsibly managed.

Perspective diversification. A purported feature of much professional metadata activity has been neutral or objective description. However, we are aware that to be 'neutral' can actually mean to be aligned with dominant perspectives. We know that metadata and subject description have very often been partial, harmful or unknowing about the resources described, or have continued obsolescent or superseded perspectives, or have not described resources or people in ways that a relevant community expects or can easily find. This may be in relation to race, gender, nationality, sexual orientation, or other contexts. This awareness leads directly into the second direction I discuss below, pluralization. It also highlights the increasing reliance on community perspectives. It is important to understand context, cultural protocols, community meanings and expectations, through more reciprocal approaches. And as noted above, use of programmatically promoted or intentional data needs to be responsibly approached, alert to ways in which preferences or bias can be present.

So we want to make metadata work harder, but we also need more metadata and more types of metadata. Metadata helps us to work in network environments.

A more formal definition of metadata might run something like: "schematized assertions about a resource of interest." However, as we think about navigating increasingly digital workflows and environments, I like to think about metadata in this general way:

data which relieves a potential user (whether human or machine) of having to have full advance knowledge of the existence or characteristics of a resource of potential interest in the environment.

Metadata allows applications and users to act more intelligently, and this becomes more important in our increasingly involved digital workflows and environments.

Given this importance, and given the importance of such digital environments to our working, learning and social lives, it also becomes more important to think about how metadata is created, who controls it, how it is used, and how it is stewarded over time. Metadata is about both value and values.

In this short piece, and in the presentation on which it is based, I limit my attention to two important directions. Certainly, this is a part only of the larger picture of evolving metadata creation, use and design in libraries and beyond.

So we want to make metadata work harder, but we also need more metadata and more types of metadata. Metadata helps us to work in network environments.

Two metadata directions

I want to talk about two important directions here.

- Entification.

- Pluralization.

Entification: strings and things

Google popularized the notion of moving from 'strings' to 'things' when it introduced the Google knowledge graph. By this we mean that it is difficult to rely on string matching for effective search, management or measurement of resources. Strings are ambiguous. What we are actually interested in are the 'things' themselves, actual entities which may be referred to in different ways.

Entification involves establishing a singular identity for 'things' so that they can be operationalized in applications, gathering information about those 'things,' and relating those 'things' to other entities of interest.

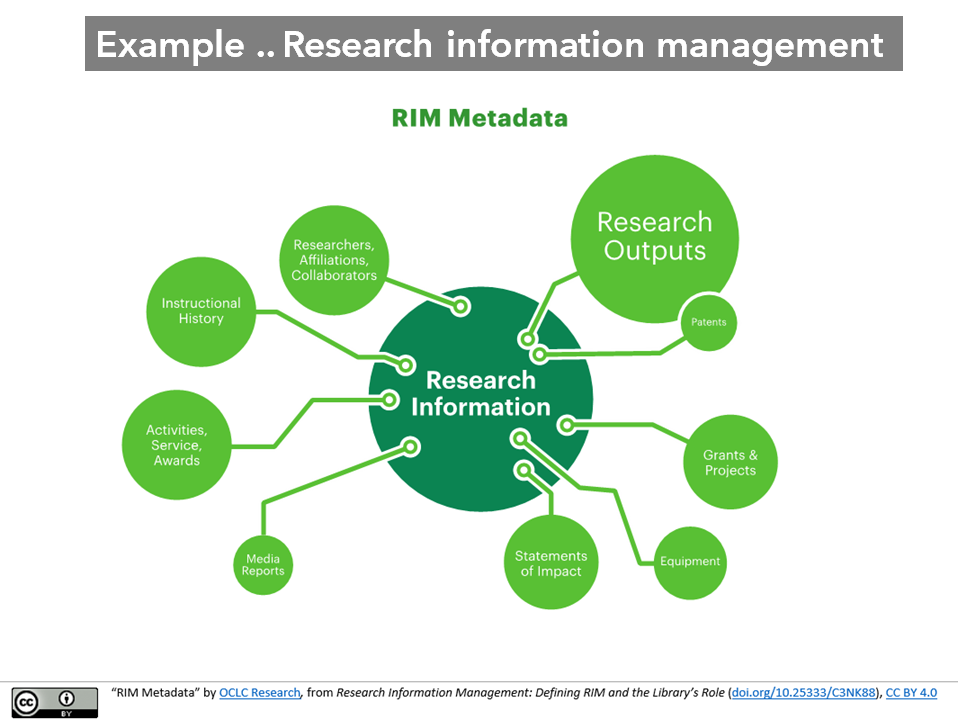

Research information management and the scholarly ecosystem provide a good example of this. This image shows a variety of entities of interest in a research information management system.

These include researchers, research outputs, institutions, grants and other entities. Relationships between these include affiliation (researcher to institution), collaborator (researcher to researcher), authorship (researcher to research output), and so on. We want to know that the professor who got this grant is the same one as the one who teaches this course or published that paper.

These identities could be (and are) established within each system or service. So, this means that a Research Information Management System does not only return strings that match a text search. It can facilitate the prospecting of a body of institutional research outputs, a set of scholars, a collection of labs and departments, and so on, and allow links to related works, scholars and institutions to be made.

Similarly, a scholarly engine like Scopus, or Semantic Scholar, or Dimensions will bring together scholarly entities and offer access to a more or less rich network of results. Of course, in this case, the metadata may be under less close control. Typically, they will also be using metadata sourced in the four ways I described above, as 'professionally created' metadata works with metadata contributed by, say, individual researchers, as entities may be established and related programmatically, and as usage data helps organize resources.

Wikidata is an important resource in this context, as a globally addressable identity base for entities of all types.

Of course one wants to work with entities across systems and services. Researchers move between institutions, collaborate with others, cite research outputs, and so on. One may need to determine whether an identity in one context refers to the same entity as an identity in another context. So important entity backbone services have emerged which allow entities to be identified across systems and services by assigning globally unique identifiers. These include Orcid for researchers, DOI for research outputs, and the emerging ROR for institutions.

These initiatives aim to create a singular identity for resources, gather some metadata about them, and make this available for other services to use. So a researcher may have an Orcid, for example, which is associated with a list of research outputs, an affiliation, and so on. This Orcid identity may then be used across services, supporting global identification and contextualization.

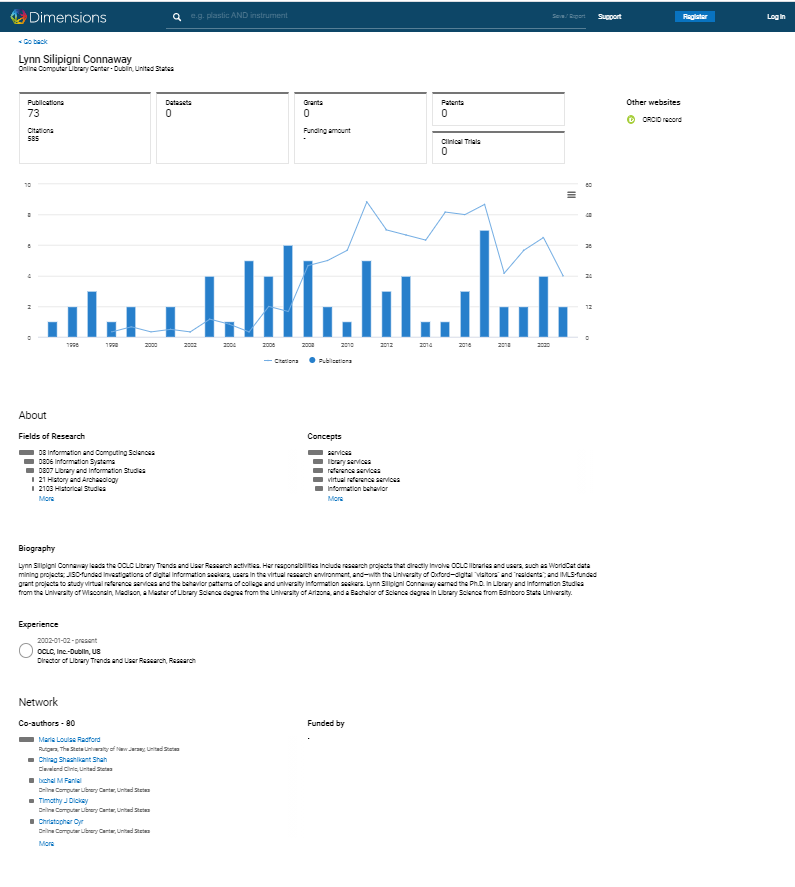

Here, for example, is a profile generated programmatically by Dimensions (from Digital Science) for my colleague Lynn Connaway. It aims to generate a description, but then also to recognize and link to other entities (e.g. topics, institutions, or collaborators). Again, the goal is to present a profile, and then to allow us to prospect a body of work and its connections. It pulls data from various places. We are accustomed to this more generally now with Knowledge Cards in Google (underpinned by Google's knowledge graph).

Of course, this is not complete, and there has been some interesting discussion about improved use of identifiers from the scholarly entity backbone services. Meadows and Jones talk about the practical advantages to scholarly communication of a 'PID-optimized world.' (PID=persistent identifier.)

In these systems and services, the entities I have been talking about will typically be nodes in an underlying knowledge graph or ontology.

Today, KGs are used extensively in anything from search engines and chatbots to product recommenders and autonomous systems. In data science, common use cases are around adding identifiers and descriptions to data of various modalities to enable sense-making, integration, and explainable analysis. [...]

A knowledge graph organises and integrates data according to an ontology, which is called the schema of the knowledge graph, and applies a reasoner to derive new knowledge. Knowledge graphs can be created from scratch, e.g., by domain experts, learned from unstructured or semi-structured data sources, or assembled from existing knowledge graphs, typically aided by various semi-automatic or automated data validation and integration mechanisms. // The Alan Turing Institute

The knowledge graph may be internal to a particular service (Google for example) or may be used within a domain or globally. Again, Wikidata is important because it publishes its underlying knowledge graph and can be used to provide context, matches, and so on for other resources.

The Library of Congress, other national libraries, OCLC ,and others now manage entity backbones for the library community, sometimes rooted in traditional authority files. There is a growing awareness of the usefulness of entity-based approaches and of the importance of identifiers in this context.

In this way, it is expected that applications will be able to work across these services. For example, an Orcid identity may be matched with identifiers from other services, VIAF for example, to provide additional context or detail, or Wikidata to provide demographic or other data not typically found in bibliographic services.

In this way, we can expect to see a decentralized infrastructure which can be tied together to achieve particular goals.

Pluralizing description

“Nobody should be compelled to us a slur to search a catalogue” - @mentionthewar #DCDC21

— David Prosser (@RLUK_David) June 29, 2021

Systems of description are inevitably both explicitly and implicitly constructed within particular perspectives. Metadata and subject description have long been criticized for embodying dominant perspectives, and for actively shunning or overlooking the experiences, memories or expectations of parts of the communities they serve. They may also contain superseded, obsolescent or harmful descriptions.

Libraries have spoken about "knowledge organization" but such a phrase has to reckon with two challenges. First, it is acknowledged that there are different knowledges.

The TK Labels support the inclusion of local protocols for access and use to cultural heritage that is digitally circulating outside community contexts. The TK Labels identify and clarify community-specific rules and responsibilities regarding access and future use of traditional knowledge. This includes sacred and/or ceremonial material, material that has gender restrictions, seasonal conditions of use and/or materials specifically designed for outreach purposes. // Local Contexts, [Traditional Knowledge] labels

Second, knowledge may be contested, where it has been constructed within particular power relations and dominant perspectives.

Others described “the look of horror” on the face of someone who has been told to search using the term “Indians of North America.” Students — Indigenous as well as settler—who work with the collections point out to staff the many incorrect or outdated terms they encounter. // Towards respectful and inclusive description

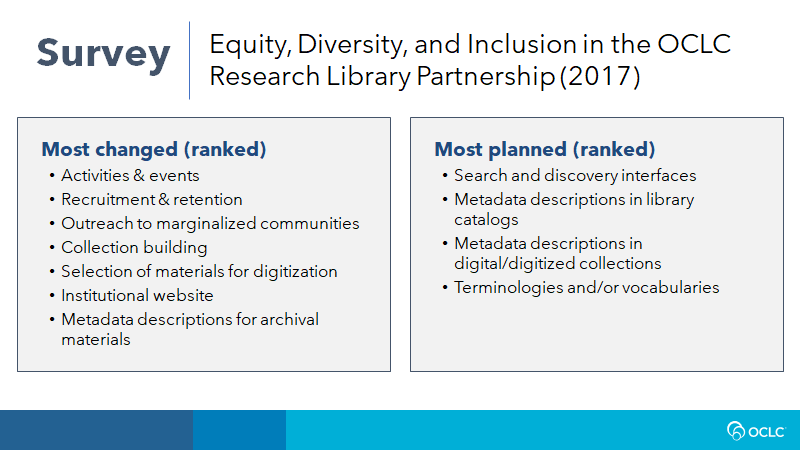

My Research Library Partnership colleagues carried out a survey on Equity, Diversity and Inclusion in 2017. While it is interesting to note the mention of archival description as among the most changed features, there was clearly a sense that metadata description and terminologies required attention, and there was an intention to address these next.

Such work may be retrospective, including remediation of existing description by linking to or substituting more appropriate descriptions. And there is certainly now a strong prospective focus, working on pluralizing description, on decentering dominant perspectives to respectfully and appropriately describe resources.

This work has been pronounced in Australia, New Zealand and Canada, countries which recognize the need to address harmful practices in relation to Indigenous populations. In early 2020, my RLP colleagues interviewed 41 library staff from 21 institutions in Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the US to talk about respectful and inclusive description:

Of those interviewed, no one felt they were doing an adequate job of outreach to communities. Several people weren’t even sure how to go about connecting with stakeholder communities. Some brought up the possibility of working with a campus or community-based Indigenous center. These organizations can be a locus for making connections and holding conversations. A few working in a university setting have found strong allies and partners to advocate for increased resources in faculty members of the Indigenous Studies department (or similar unit). Those with the most developed outreach efforts saw those activities as being anchored in exchanges that originated at the reference desk, such as when tribal members came into the library to learn something about their own history, language or culture using materials that are stewarded by the library. Engaging with these communities to understand needs offers the opportunity to transform interactions with them from one-time transactions to ongoing, meaningful relationships. Learning how Indigenous community members use and relate to these materials can decenter default approaches to description and inspire more culturally appropriate ways. Some institutions have developed fellowships to foster increased use of materials by community members. // Towards respectful and inclusive description

The murder of George Floyd in the US caused a general personal, institutional and community reckoning with racism. This has extended to addressing bias in library collections and descriptions.

Materials in our collections, which comprise a part of the cultural and historical record, may depict offensive and objectionable perspectives, imagery, and norms. While we have control over description of our collections, we cannot alter the content. We are committed to reassessing and modifying description when possible so that it more accurately and transparently reflects the content of materials that are harmful and triggering in any way and for any reason.

As librarians and archivists at NYU Libraries, we are actively confronting and remediating how we describe our collection materials. We know that language can and does perpetuate harm, and the work we are undertaking centers on anti-oppressive practices. We are also making reparative changes, all to ensure that the descriptive language we use upholds and enacts our values of inclusion, diversity, equity, belonging, and accessibility. // NYU Libraries, Archival Collections Management, Statement on Harmful Language.

Many individual libraries, archives and other organizations are now taking steps to address these issues in their catalogs. The National Library of Scotland has produced an interesting Inclusive Terminology guide and glossary, which includes a list of areas of attention.

Of course, the two directions I have mentioned can be connected, as entification and linking strategies may offer ways of pluralizing description in the future:

Other magic included technical solutions, such as linked data solutions, specifically, mapping inappropriate terms to more appropriate ones, or connecting the numerous alternative terms with the single concept they represent. For example, preferred names and terms may vary by community, generation, and context—what is considered incorrect or inappropriate may be a matter of perspective. Systems can also play a role: the discovery layers should have a disclaimer stating that users may find terms that are not currently considered appropriate. Terms that are known to be offensive terms could be blurred out (with an option to reveal them). // Towards respectful and inclusive description

OCLC Initiatives

Now I will turn to discuss one important initiative OCLC has under each of these two directions.

Entification at OCLC: towards a shared entity management infrastructure

For linked data to move into common use, libraries need reliable and persistent identifiers and metadata for the critical entities they rely on. This project [SEMI] begins to build that infrastructure and advances the whole field // Lorcan Dempsey

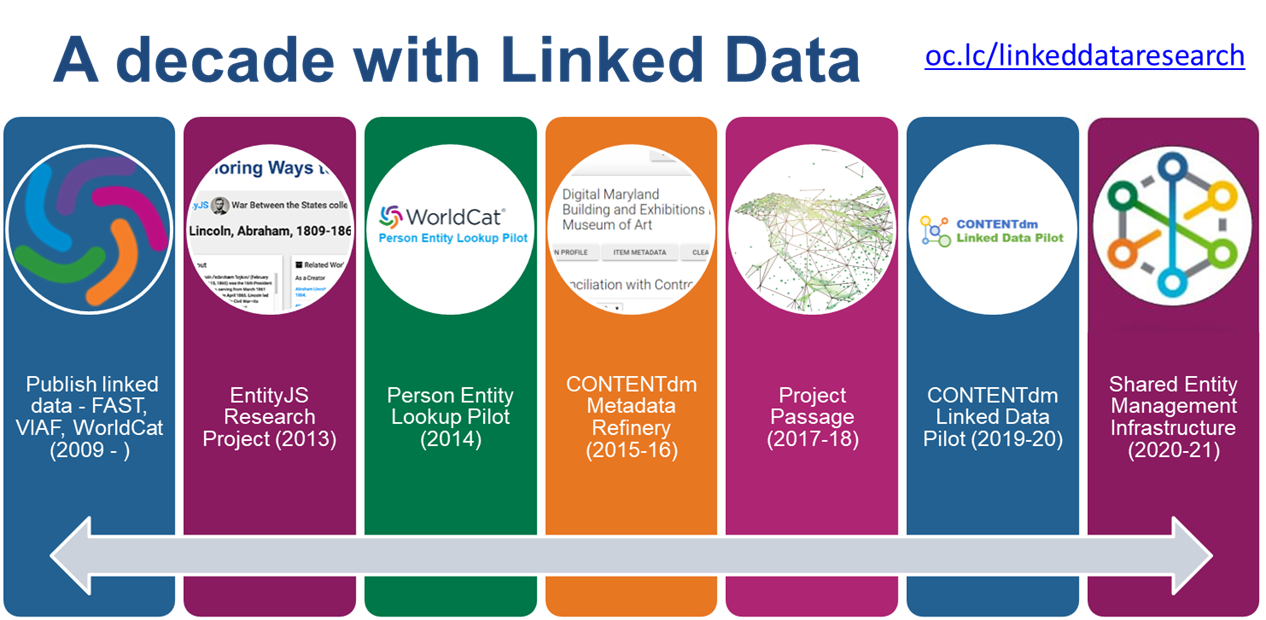

OCLC has long worked with entification in the context of several linked data initiatives. VIAF (the Virtual International Authority File) has been foundational here. This brings together name authority files from national libraries around the world, and establishes a singular identity for persons across them. It adds bibliographic and other data for context. And it matches to some other identifiers. VIAF has become an important source of identity data for persons in the library community.

Project Passage is also an important landmark. In this project we worked with Wikibase to experiment with linked data and entification at scale. My colleague Andrew Pace provides an overview of the lessons learned:

- The building blocks of Wikibase can be used to create structured data with a precision that exceeds current library standards.

- The Wikibase platform enables user-driven ontology design but raises concerns about how to manage and maintain ontologies.

- The Wikibase platform, supplemented with OCLC’s enhancements and stand-alone utilities, enables librarians to see the results of their effort in a discovery interface without leaving the metadata-creation workflow.

- Robust tools are required for local data management. To populate knowledge graphs with library metadata, tools that facilitate the import and enhancement of data created elsewhere are recommended.

- The pilot underscored the need for interoperability between data sources, both for ingest and export.

- The traditional distinction between authority and bibliographic data disappears in a Wikibase description.

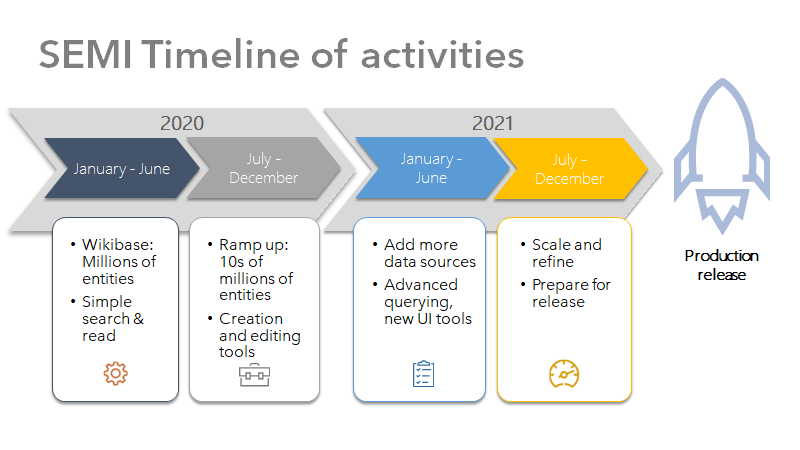

These initiatives paved the way for SEMI (Shared Entity Management Infrastructure). Supported by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, SEMI is building the infrastructure which will support OCLC's production entity management services. The goal is to have infrastructure which allows libraries to create, manage and use entity data at scale. The initial focus is on providing infrastructure for work and person entities. It is advancing with input from a broad base of partners and a variety of data inputs, and will be released for general use in 2022.

Pluralization at OCLC: towards reimagining descriptive workflows

OCLC recognizes its important role in the library metadata environment and has been reviewing its own vocabulary and practices. For example, it has deprecated the term 'master record' in favor of 'WorldCat record.'

It was also recognized that there were multiple community and institutional initiatives which were proceeding independently and that there would be value in a convening to discuss shared directions.

Accordingly, again supported by the Andrew W Mellon Foundation, OCLC, in consultation with Shift Collective and an advisory group of community leaders, is developing a program to consider these issues at scale. The following activities are being undertaken over several months:

- Convene a conversation of community stakeholders about how to address the systemic issues of bias and racial equity within our current collection description infrastructure.

- Share with member libraries the need to build more inclusive and equitable library collections and to provide description approaches that promote effective representation and discovery of previously neglected or mis-characterized peoples, events, and experiences.

- Develop a community agenda that will be of great value in clarifying issues for those who do knowledge work in libraries, archives, and museums, identifying priority areas for attention from these institutions, and providing valuable guidance for those national agencies and suppliers.

It is hoped that the community agenda will help mobilize activity across communities of interest, and will also provide useful input into OCLC development directions.

Find out more .. resources to check out

The OCLC Research Library Partners Metadata Managers Focus Group is an important venue for discussion of metadata directions and community needs. This report synthesizes six years (2015-2020) of discussion, and traces how metadata services are evolving:

This post brings together a series of international discussions about the report and its ramifications for services, staffs and organization.

Next-generation metadata and the semantic continuum

For updates about OCLC's SEMI initiative, see here:

For more about about reimagining descriptive workflows, see here:

The Project Passage summary and report is here:

Acknowledgements: Thanks to my colleagues John Chapman, Rachel Frick, Erica Melko, Andrew Pace and Merrilee Proffitt for providing material and/or advice as I prepared the presentation and this entry. Again, thanks to April Manabat of Nazarbayev University for the invitation and for encouragement along the way. For more information about the Conference, check out these pages:

Picture: I took the feature picture at Sydney Airport, Australia (through a window). The Pandemic is affecting how we think about work travel and the design of events, although in as yet unclear ways. One pandemic effect, certainly, has been the ability to think about both audiences and speakers differently. It is unlikely that I would have attended this conference had it been face to face, however, I readily agreed to be an online participant.